|

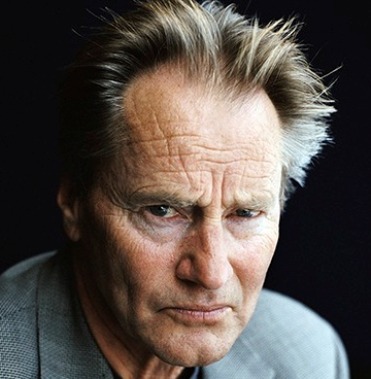

| Alberto Giacometti, Rimbaud |

Comme je descendais des Fleuves impassibles,

Je ne me sentis plus guidé par les haleurs :

Des Peaux-rouges criards les avaient pris pour cibles,

Les ayant cloués nus aux poteaux de couleurs.

J'étais insoucieux de tous les équipages,

Porteur de blés flamands ou de cotons anglais.

Quand avec mes haleurs ont fini ces tapages,

Les Fleuves m'ont laissé descendre où je voulais.

Dans les clapotements furieux des marées,

Moi, l'autre hiver, plus sourd que les cerveaux d'enfants,

Je courus ! Et les Péninsules démarrées

N'ont pas subi tohu-bohus plus triomphants.

La tempête a béni mes éveils maritimes.

Plus léger qu'un bouchon j'ai dansé sur les flots

Qu'on appelle rouleurs éternels de victimes,

Dix nuits, sans regretter l'œil niais des falots !

Plus douce qu'aux enfants la chair des pommes sures,

L'eau verte pénétra ma coque de sapin

Et des taches de vins bleus et des vomissures

Me lava, dispersant gouvernail et grappin.

Et dès lors, je me suis baigné dans le Poème

De la Mer, infusé d'astres, et lactescent,

Dévorant les azurs verts ; où, flottaison blême

Et ravie, un noyé pensif parfois descend ;

Où, teignant tout à coup les bleuités, délires

Et rythmes lents sous les rutilements du jour,

Plus fortes que l'alcool, plus vastes que nos lyres,

Fermentent les rousseurs amères de l'amour !

Je sais les cieux crevant en éclairs, et les trombes

Et les ressacs et les courants : je sais le soir,

L'Aube exaltée ainsi qu'un peuple de colombes,

Et j'ai vu quelquefois ce que l'homme a cru voir !

J'ai vu le soleil bas, taché d'horreurs mystiques,

Illuminant de longs figements violets,

Pareils à des acteurs de drames très antiques

Les flots roulant au loin leurs frissons de volets !

J'ai rêvé la nuit verte aux neiges éblouies,

Baiser montant aux yeux des mers avec lenteurs,

La circulation des sèves inouïes,

Et l'éveil jaune et bleu des phosphores chanteurs !

J'ai suivi, des mois pleins, pareille aux vacheries

Hystériques, la houle à l'assaut des récifs,

Sans songer que les pieds lumineux des Maries

Pussent forcer le mufle aux Océans poussifs !

J'ai heurté, savez-vous, d'incroyables Florides

Mêlant aux fleurs des yeux de panthères à peaux

D'hommes ! Des arcs-en-ciel tendus comme des brides

Sous l'horizon des mers, à de glauques troupeaux !

J'ai vu fermenter les marais énormes, nasses

Où pourrit dans les joncs tout un Léviathan !

Des écroulements d'eaux au milieu des bonaces,

Et des lointains vers les gouffres cataractant !

Glaciers, soleils d'argent, flots nacreux, cieux de braises !

Échouages hideux au fond des golfes bruns

Où les serpents géants dévorés des punaises

Choient, des arbres tordus, avec de noirs parfums !

J'aurais voulu montrer aux enfants ces dorades

Du flot bleu, ces poissons d'or, ces poissons chantants.

− Des écumes de fleurs ont bercé mes dérades

Et d'ineffables vents m'ont ailé par instants.

Parfois, martyr lassé des pôles et des zones,

La mer dont le sanglot faisait mon roulis doux

Montait vers moi ses fleurs d'ombre aux ventouses jaunes

Et je restais, ainsi qu'une femme à genoux...

Presque île, ballottant sur mes bords les querelles

Et les fientes d'oiseaux clabaudeurs aux yeux blonds.

Et je voguais, lorsqu'à travers mes liens frêles

Des noyés descendaient dormir, à reculons !

Or moi, bateau perdu sous les cheveux des anses,

Jeté par l'ouragan dans l'éther sans oiseau,

Moi dont les Monitors et les voiliers des Hanses

N'auraient pas repêché la carcasse ivre d'eau ;

Libre, fumant, monté de brumes violettes,

Moi qui trouais le ciel rougeoyant comme un mur

Qui porte, confiture exquise aux bons poètes,

Des lichens de soleil et des morves d'azur ;

Qui courais, taché de lunules électriques,

Planche folle, escorté des hippocampes noirs,

Quand les juillets faisaient crouler à coups de triques

Les cieux ultramarins aux ardents entonnoirs ;

Moi qui tremblais, sentant geindre à cinquante lieues

Le rut des Béhémots et les Maelstroms épais,

Fileur éternel des immobilités bleues,

Je regrette l'Europe aux anciens parapets !

J'ai vu des archipels sidéraux ! et des îles

Dont les cieux délirants sont ouverts au vogueur :

− Est-ce en ces nuits sans fonds que tu dors et t'exiles,

Million d'oiseaux d'or, ô future Vigueur ?

Mais, vrai, j'ai trop pleuré ! Les Aubes sont navrantes.

Toute lune est atroce et tout soleil amer :

L'âcre amour m'a gonflé de torpeurs enivrantes.

O que ma quille éclate ! O que j'aille à la mer !

Si je désire une eau d'Europe, c'est la flache

Noire et froide où vers le crépuscule embaumé

Un enfant accroupi plein de tristesse, lâche

Un bateau frêle comme un papillon de mai.

Je ne puis plus, baigné de vos langueurs, ô lames,

Enlever leur sillage aux porteurs de cotons,

Ni traverser l'orgueil des drapeaux et des flammes,

Ni nager sous les yeux horribles des pontons.